Korean Salt Cheonil-yeom (천일염)

What Is Korean Cheonil-yeom (천일염)? Cheonil-yeom (천일염) literally means “sun-dried salt.” It refers to sea salt naturally evaporated using sunlight and wind, primarily produced along the west coast of Korea,…

KFoodinUS.com uses your location to personalize your experience and provide relevant local content. By allowing access, you consent to our use of location data in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can update your preferences at any time.

Today is February 9, 2026. We couldn't detect your location. Please allow location access.

Korean temple food is a plant-based, minimalist cuisine developed and refined by Buddhist monks over centuries. Rooted in the principles of non-violence, mindfulness, and harmony with nature, it’s one of the oldest and healthiest food traditions in Korea.

Temple food refers to the meals prepared and eaten in Buddhist temples across Korea. It is:

| Category | Ingredients |

|---|---|

| Grains | Rice, barley, millet |

| Vegetables | Fernbrake (gosari), bellflower root (doraji), lotus root |

| Legumes | Soybeans (for tofu, soy paste), mung beans |

| Ferments | Doenjang (soybean paste), gochujang, soy sauce |

| Pickles | Kimchi (without garlic), jangajji (soy-pickled veg) |

| Special dishes | Lotus leaf rice, tofu stew, pan-fried root vegetables |

Korean temple food is nutritionally dense and low in calories due to its focus on:

Multiple scientific studies (particularly those by the Temple Food Research Institute) have linked temple food to benefits like:

Temple food is not just about nutrition — it’s a spiritual and ethical way of eating:

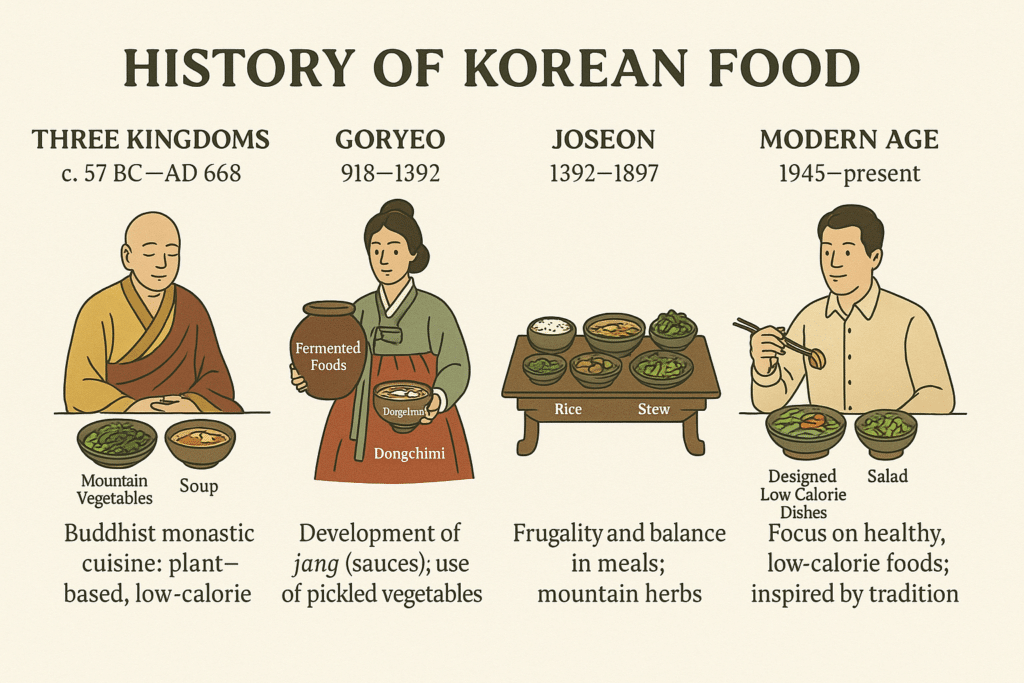

The history of Korean food is deeply tied to Korea’s geography, climate, historical hardships, and cultural values like balance and harmony. Its development—especially the focus on low-calorie, plant-based dishes and mountain vegetables—stems from both necessity and philosophy.

| Factor | Contribution to Low-Calorie Cuisine |

|---|---|

| Mountainous terrain | More wild vegetables, less reliance on meat |

| Buddhist influence | Plant-based, mindful eating |

| Food scarcity | Smaller portions, meat used as seasoning not main |

| Fermentation and preservation | Long-lasting, low-calorie condiments like kimchi |

| Confucian/medical principles | Balanced, moderate meals with varied plant intake |

Korea’s natural environment — particularly its mountain-fed water systems and abundant wild edible plants — has long contributed to the distinctiveness and perceived purity of Korean cuisine. Here’s why they’re considered special:

In Korea, yaksu-mul (약수물) refers to natural mineral spring water believed to have health-promoting properties. These waters, found throughout the country—especially in mountainous regions—have been consumed for centuries as a form of natural therapy, and are still popular among locals and visitors seeking holistic well-being.

| Belief | Expected Benefit |

|---|---|

| “Clears the stomach” | Aids digestion, reduces acid |

| “Boosts energy” | Refreshes and revitalizes, especially after hiking |

| “Strengthens the body” | High mineral content thought to improve resilience |

| “Good for skin” | Some sources used for facial rinsing or soaking |

Although not all claims are medically verified, the clean and crisp taste, along with a cultural belief in nature-based healing, keeps the tradition alive.

Here are some of Korea’s most well-known medicinal spring water sources:

약수물 reflects Koreans’ deep respect for nature and traditional beliefs in healing through the environment. It blends folk medicine, daily habit, and spiritual wellness—an extension of the idea that “food and water are medicine.”

In the heart of Korea’s mountainous landscape grows a unique culinary tradition — sannamul (산나물), or wild mountain greens. More than just food, these foraged herbs and plants are a seasonal ritual, a health tonic, and a symbol of Korea’s enduring connection to nature. Harvested in early spring and fall, sannamul plays a central role in Korean home cooking, temple cuisine, and traditional medicine.

Sannamul refers to a variety of wild edible plants that grow naturally in Korea’s forests and mountains. Unlike cultivated vegetables, these greens are foraged, not farmed — often hand-picked by elders, monks, or seasoned gatherers.

They are typically:

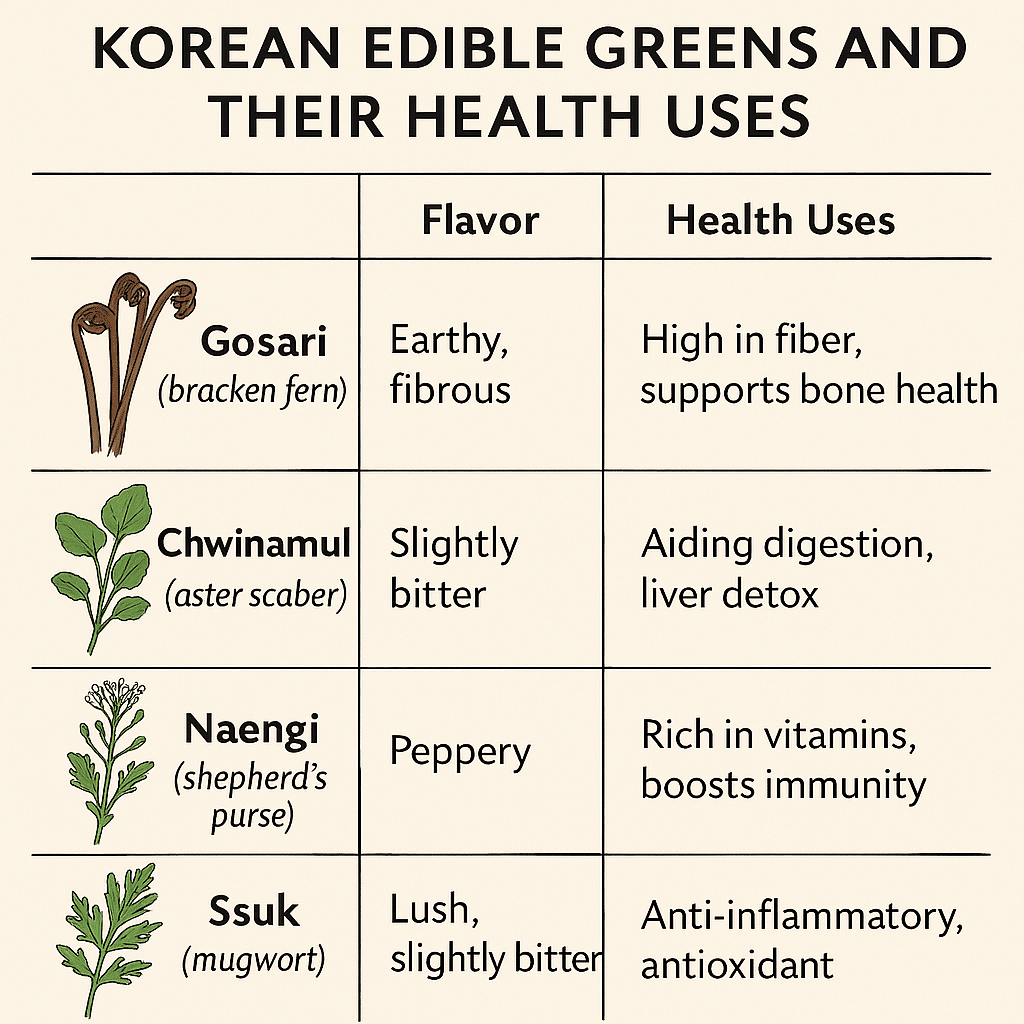

| Name (Korean / English) | Flavor Profile | Common Uses | Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gosari (고사리) – Bracken fern | Earthy, chewy | Bibimbap, stir-fry | High in fiber, supports bone health |

| Chwinamul (취나물) – Aster scaber | Slightly bitter | Seasoned side dish | Liver detox, digestive aid |

| Naengi (냉이) – Shepherd’s purse | Peppery, nutty | Soybean paste soup | Vitamin-rich, immunity support |

| Dureup (두릅) – Angelica tree shoots | Soft, aromatic | Blanched, seasoned | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant |

| Ssuk (쑥) – Mugwort | Herbal, slightly bitter | Rice cakes, soups | Anti-inflammatory, improves circulation |

Simplicity is key — traditional Korean cooking avoids overpowering the greens’ natural flavors.

Common preparations include:

In Korean Buddhist temples, sannamul is a cornerstone of vegan temple food. Monks forage these herbs themselves and prepare them without meat, garlic, or strong spices. The goal is harmony with nature and inner peace — and mountain greens are seen as both nourishment and medicine.

Sannamul isn’t just about taste — it’s about time, place, and tradition. Eating these wild greens is a way to participate in a centuries-old Korean practice of seasonal living, reverence for nature, and food as medicine. Whether you try them in a bibimbap bowl or at a temple table, sannamul offers a flavorful path into the heart of Korean heritage.

Korea’s biodiversity, especially in its mountainous and forested regions, has given rise to a distinct culture of foraging and seasonal greens, many of which are tied to traditional medicine.

| Element | Uniqueness in Korea |

|---|---|

| Water | Soft, mountain-spring fed; enhances food & fermentation |

| Cleanliness | Advanced filtration systems; safe for drinking; spring culture |

| Edible Plants | Wild herbs deeply integrated into cuisine and medicine |

| Philosophy | Eating seasonally, ethically, and in harmony with nature |

What Is Korean Cheonil-yeom (천일염)? Cheonil-yeom (천일염) literally means “sun-dried salt.” It refers to sea salt naturally evaporated using sunlight and wind, primarily produced along the west coast of Korea,…

Your Korean friend in her mid-30s has the skin of someone at least 10 years…

Explore the rich traditions and etiquette of Korean food culture, from communal dining and fiery…

Discover 9 science-backed health benefits of kimchi—from boosting gut health to supporting immunity—and why making…

Korean food developed a strong culture of preserved food (jeojang eumsig, 저장 음식) and fermented food (balhyo eumsig, 발효 음식) due to a combination of historical necessity, environmental challenges, and health philosophy. Here’s how it unfolded and what it means today:

| Food | Description | Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Kimchi (김치) | Fermented napa cabbage with chili, garlic, and fish sauce | Probiotics, vitamins A & C, anti-inflammatory, supports gut health |

| Doenjang (된장) | Fermented soybean paste | Rich in enzymes, boosts immunity, gut health, anti-cancer potential |

| Ganjang (간장) | Naturally brewed soy sauce | Contains amino acids, antioxidants |

| Gochujang (고추장) | Fermented red pepper paste with rice, barley malt, and soybeans | Supports metabolism, adds probiotics |

| Cheonggukjang (청국장) | Quick-fermented soybeans, pungent smell | High in protein, gut flora support, reduces cholesterol |

| Fermented vinegar (식초) | Made from fermented grains, fruits, or rice | Aids digestion, detoxifying effect |

| Makgeolli (막걸리) | Traditional fermented rice wine | Contains lactobacillus, vitamins B1 & B2 (in moderation) |

Korea’s tradition of fermented foods was born from necessity, but evolved into a core of Korean culinary identity and health practice. Today, these foods are gaining global attention as natural probiotics and superfoods — not only tasty, but therapeutic.

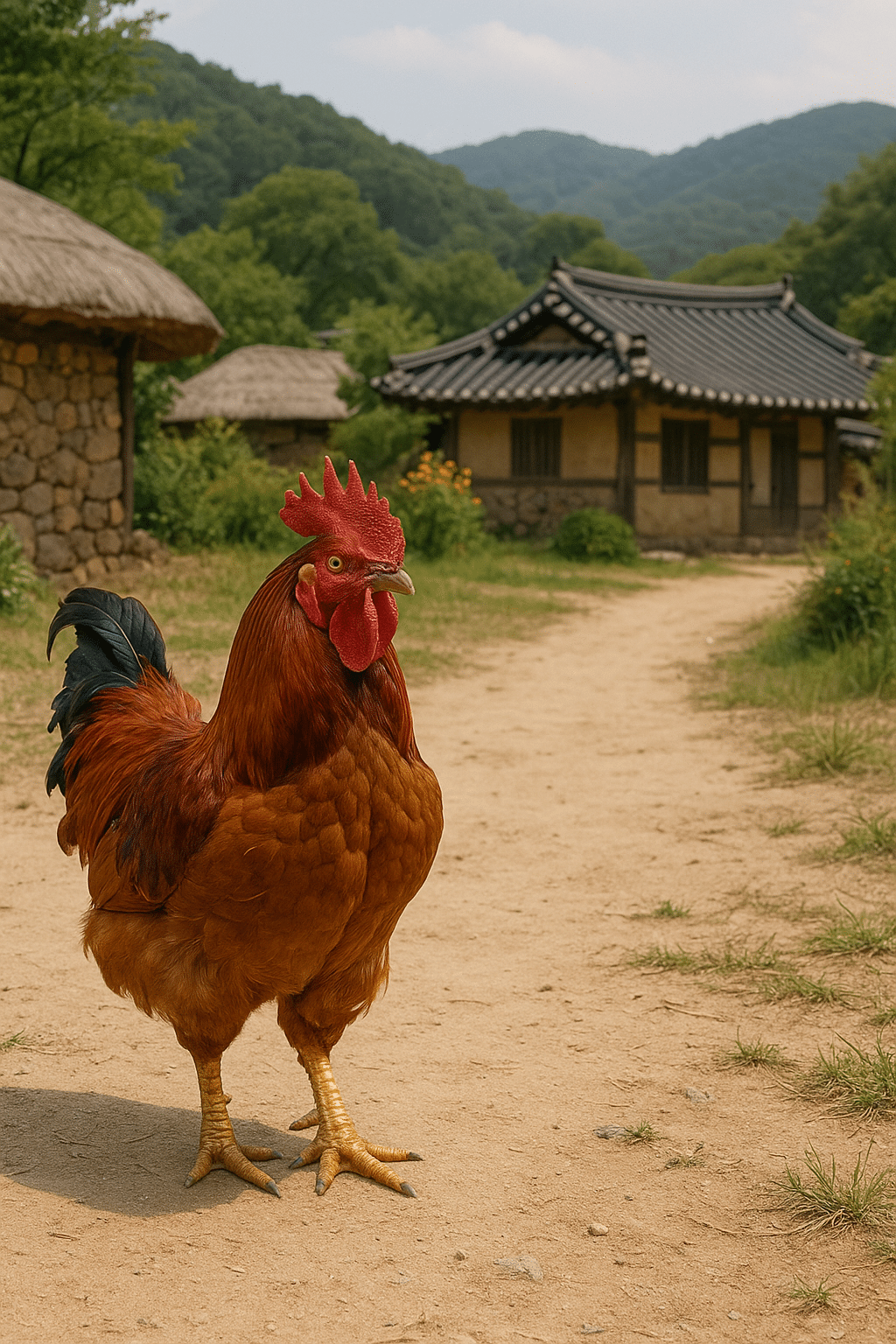

Samgyetang (삼계탕) is a traditional Korean dish made by simmering a whole young chicken stuffed with glutinous rice, garlic, jujubes (Korean dates), and ginseng in a flavorful broth. The soup is gently boiled until the chicken becomes fall-off-the-bone tender and infused with medicinal herbs.

It is served hot, and diners are encouraged to eat the rice stuffing, sip the rich broth, and enjoy the soft, nourishing meat together.

It may seem counterintuitive, but samgyetang is traditionally eaten during the hottest days of summer, known as “Sambok (삼복)” days:

This practice is called “yi yeol chi yeol” (이열치열) — meaning “fight heat with heat”. The belief is that by raising the body’s internal temperature with hot food, you can:

Samgyetang is often seen as Korea’s ultimate summer stamina food.

Samgyetang is considered a nutritional powerhouse:

| Ingredient | Health Benefit |

|---|---|

| Ginseng | Boosts immunity, reduces fatigue, anti-inflammatory |

| Garlic | Improves circulation, strengthens the immune system |

| Jujubes | Rich in antioxidants and vitamin C, supports digestion |

| Glutinous rice | Provides slow-releasing energy |

| Young chicken | High in protein and easy to digest |

Because of its combination of protein, medicinal herbs, and warm broth, samgyetang is often recommended to those recovering from illness or fatigue.

Samgyetang is more than just soup — it’s a deeply rooted tradition that blends seasonal wisdom, medicinal ingredients, and comfort in one warm bowl. Whether you’re braving the summer heat or just seeking rejuvenation, this iconic Korean dish continues to nourish both body and soul.

Korean ginseng, also known as Panax ginseng or Goryeo Insam (고려인삼), is globally renowned for its potent medicinal properties, high quality, and deep historical roots. Among all ginseng-producing nations, Korean ginseng is considered the gold standard, thanks to its climate, cultivation methods, and centuries of experience.

The word “Goryeo (고려)” refers to the ancient Korean kingdom that ruled from the 10th to the 14th century. It is the origin of the modern name “Korea.”

Korean ginseng is classified as an adaptogen — a natural substance that helps the body resist stress and restore balance.

| Function | Health Effect |

|---|---|

| Immune support | Enhances resistance to illness and infection |

| Energy boost | Reduces fatigue and increases physical stamina |

| Cognitive function | Improves memory, focus, and mental clarity |

| Blood circulation | Aids in lowering blood pressure and improving blood flow |

| Anti-inflammatory | Supports recovery and reduces chronic inflammation |

Ginseng farming is labor-intensive and time-consuming:

This slow and deliberate method is why Korean ginseng commands a higher value than ginseng from other regions like China or North America.

| Type | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Insam (인삼) | Cultivated ginseng grown under human management | Widely available, consistent potency |

| Sansam (산삼) | Wild ginseng that grows naturally in mountains | Extremely rare, more potent, very expensive |

Korean legends tell of mountain spirits who gifted ginseng to wise men or wounded travelers:

These stories reflect the deep spiritual and healing symbolism of ginseng in Korean tradition.

Goryeo Insam is not just a health supplement — it’s a symbol of Korea’s resilience, natural heritage, and global legacy. Whether in modern tonic form or as part of ancient trade routes, Korean ginseng continues to embody the strength and vitality it has offered for centuries.

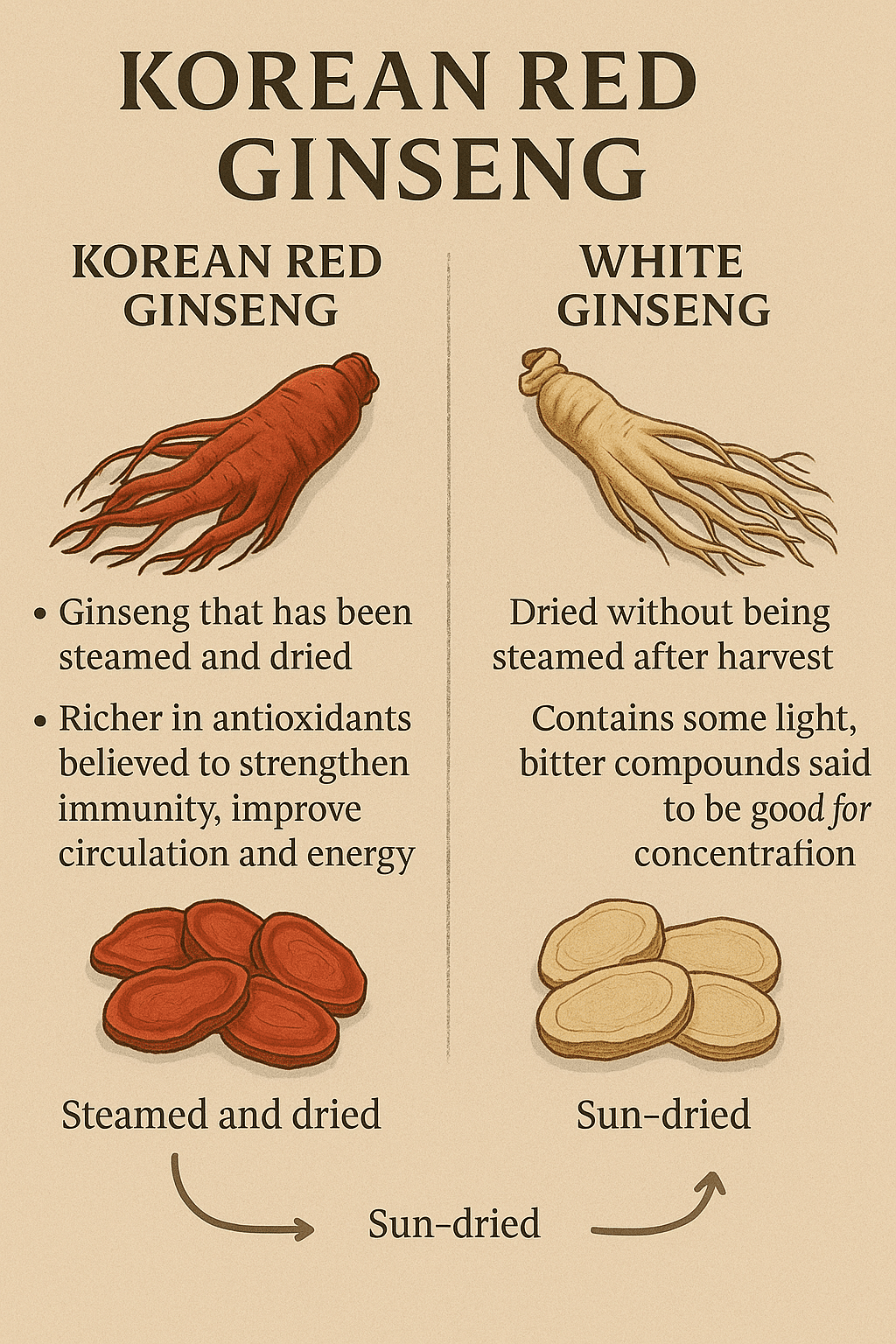

Hong-sam (홍삼) refers to red ginseng, a form of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng) that has been steamed and dried, giving it a reddish-brown color. It is known for its stronger medicinal properties, longer shelf life, and more concentrated active compounds compared to fresh or white ginseng.

| Feature | White Ginseng (백삼) | Red Ginseng (홍삼) |

|---|---|---|

| Processing | Sun-dried raw ginseng | Steamed and dried repeatedly |

| Appearance | Pale, cream-colored | Dark red or amber-brown |

| Taste | Mild and slightly bitter | Earthy, richer, and more bitter |

| Potency | Moderate | Higher concentration of ginsenosides |

| Shelf life | Shorter | Longer and more stable |

| Usage | General health maintenance | Often used for fatigue recovery, immune boosting, and chronic conditions |

Red ginseng is considered especially effective for:

It is widely used in Korea in the form of:

Korean red ginseng, or hong-sam, is a refined, more potent version of traditional ginseng with centuries of proven benefits. Through steaming and careful processing, it becomes a powerful ally in modern health — blending ancient wisdom with scientific validation.